Flash, Sweat, and 7-Eleven Prints: Surviving a Bruce Gilden Workshop

Nine years ago, I stumbled upon a Vice video featuring Bruce Gilden critiquing amateur photographs. His feedback was sharp, unflinching, and brutal. It captivated me. I knew then that if I ever had the chance to learn from him, it would be painful—and exactly what I needed.

By early 2025, my photo gigs in Tokyo were picking up. I’d been shooting nightlife for a few years and felt it was time for professional advice. It wasn’t that I wasn’t taking risks, but it isn't every day you can show your portfolio to a Magnum photographer. I signed up for the Fotofilmic workshop in Osaka because I needed someone who wouldn’t sugarcoat the work.

Rain, Rejection, and the Reality of Monday

When I arrived, Osaka was cold and rainy. The class was a mixed group: people who understood the critique style, and others who clearly didn’t expect the bluntness. Bruce looked at my portfolio—years of shooting nightlife and Tokyo streets narrowed down to a handful of prints I had made at the 7-Eleven on the cheapest paper they had.

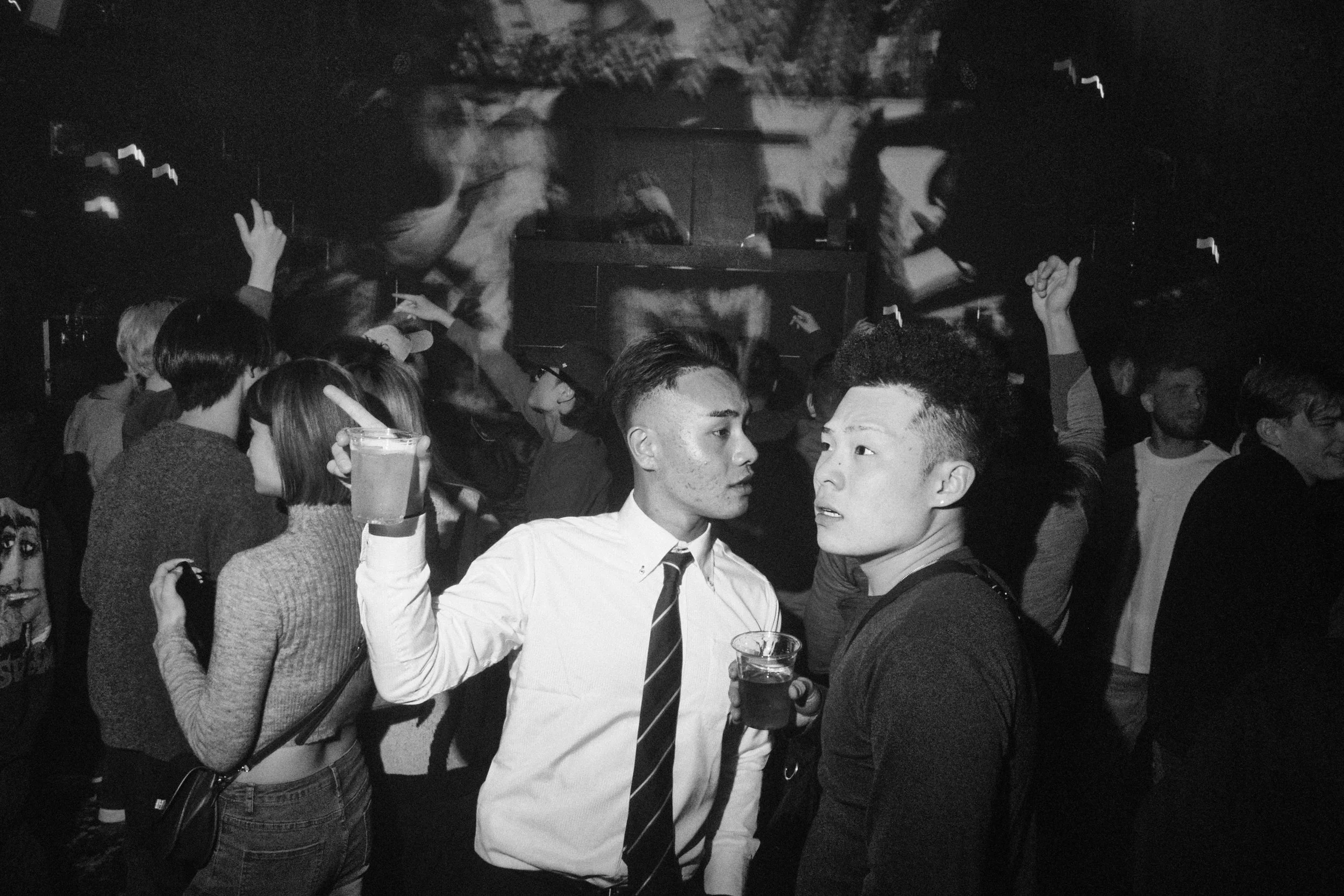

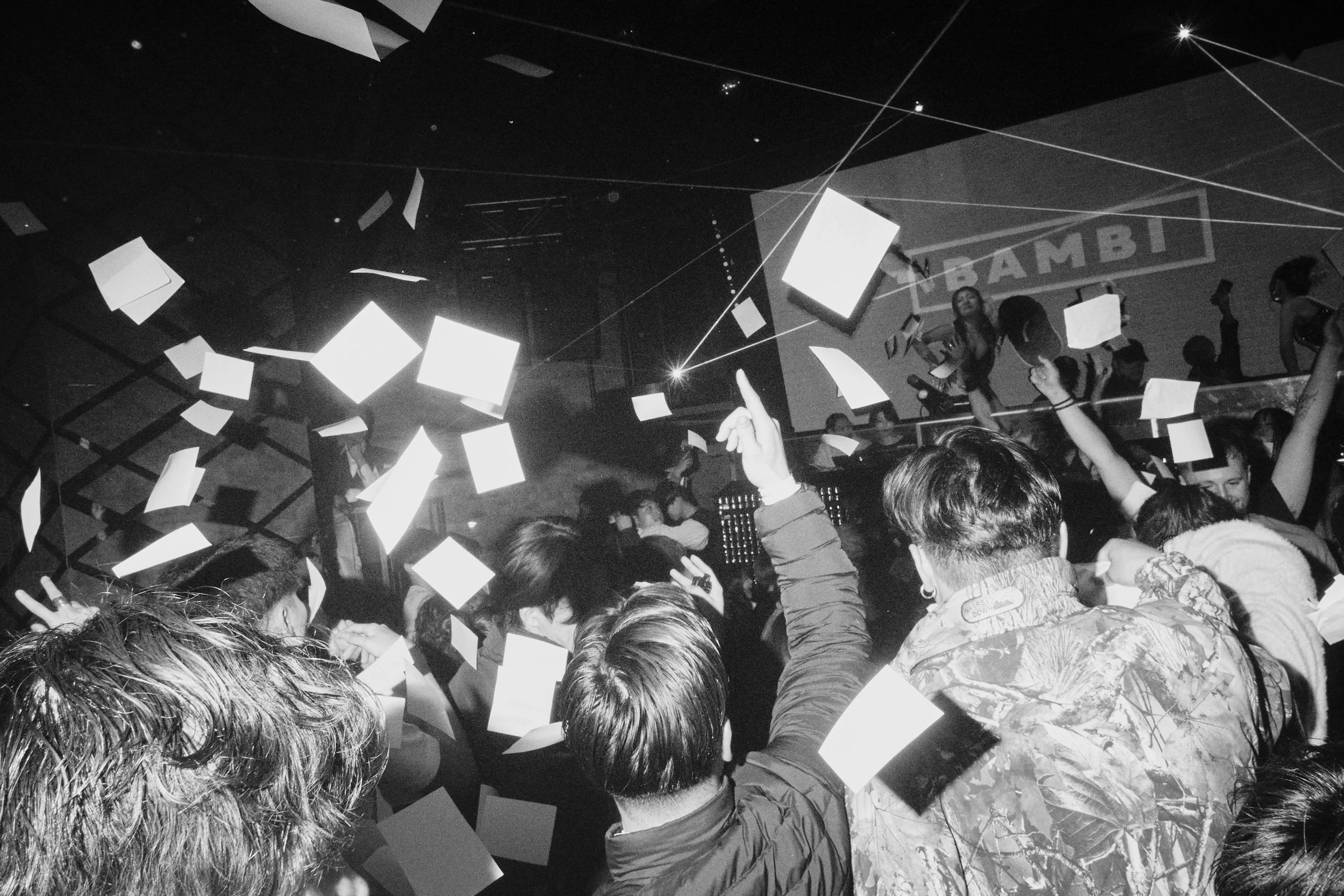

He seemed drawn to the club stuff. He told me to dig deeper into that specific niche. My assignment was nightclubs.

The problem? My shooting days were Monday through Thursday. The streets were slick with rain, and the clubs felt subdued. Osaka on a rainy March Monday is not the underworld I had fantasized about. It was quiet. The clubs were filled with fresh-faced, recently graduated university students, drinking politely in circles.

No chaos. No edge. And without crowds to disappear into, I stuck out instantly. One look at my camera plus an off-camera flash, and security treated me like a walking liability which led to getting kicked out of some spots.

The Cycle

It forced an uncomfortable truth: shooting nightlife isn’t just timing and technique. It’s social fluency. On dead nights, you’re the main event whether you want to be or not.

The schedule was a grueling cycle:

9:00 AM: Critique sessions.

Daytime: Brief, fitful sleep.

Night: Shoot until 5:00 AM.

Early Morning: Rush to the hotel, edit through bleary eyes, and present something coherent hours later.

Undeterred, I gravitated toward Super Pink a number of times, a venue with all-you-can-drink specials and performers known as "pink dancers." Elegantly dressed and welcoming, they became my willing subjects, their poise cutting through the dim lights and didn’t seem to have a problem with my flash.

This was my first real attempt at off-camera flash, and it showed. Overexposed highlights plagued my shots—a technical flaw Bruce pointed out with ‘kind’, repetitive, precision every morning. I was struggling to balance the technical demands of the flash with the candid nature of the environment.

As the week ground on, sleep deprivation blurred reality. I was exhausted, physically and mentally, but the fear of showing up empty-handed kept me showing up to Osaka’s nightclubs, stuffing my gloves and raincoat into locker rooms, and getting back to work each night.

Decoding the Simplicity

Gilden wasn’t hands-on. He didn’t hover or spoon-feed me advice from the corner of the club. He let you shoot however you wanted, then sliced into the results the next morning. His language was simple, blunt, and easy to dismiss if you didn’t listen hard enough. But once you learned to decode him, the logic was clean.

He told me I was good up close, but weak at other distances. He told me the photos were flat because the intention behind them was flat. They were echoes more than observations. Most mornings, Bruce dismantled my work. But it wasn't the technical failure that hurt the most; it was the creative one.

Then came the critique that changed everything. Bruce looked at my spread of photos and said:

"It feels like I’m looking at the same image every time."

That was the moment. Bruce recommended I look at Seiji Kurata’s Flash Up and Larry Fink’s event photography. He pushed me to draw inspiration from the greats and to start seeing the scene as it actually was, not as I wanted it to be.

Expanding the Visual Vocabulary

The week didn't fix me, nor did I leave with a portfolio of masterpieces. Instead, I realized that my visual vocabulary was too small. I had been trying to paint with only one color.

The "failure" wasn't that I was a bad photographer; it was that I hadn't done my homework. I needed to dig deeper into the history of the medium, to find inspiration in more references than just the man sitting at the head of the table.

"Honesty" in photography is often sold as candidness—catching a subject unaware. But the real honesty is recognizing the limits of your own visual language. I knew the masters, but I wasn't leveraging them. I was trapped in an echo chamber of my own making, reciting the same visual sentences over and over.

Need an Outside Eye?

Bruce Gilden tore my work apart so I could build it back better. You can’t edit your own work in a vacuum. If you’re stuck in an echo chamber or need honest feedback on your sequencing and selection, book a portfolio review. I won’t destroy you, but I won’t lie to you either.

If you’re in Tokyo and want to learn how to navigate the chaos, manage the flash, and get close without losing your nerve, join me on the pavement.